TL;DR

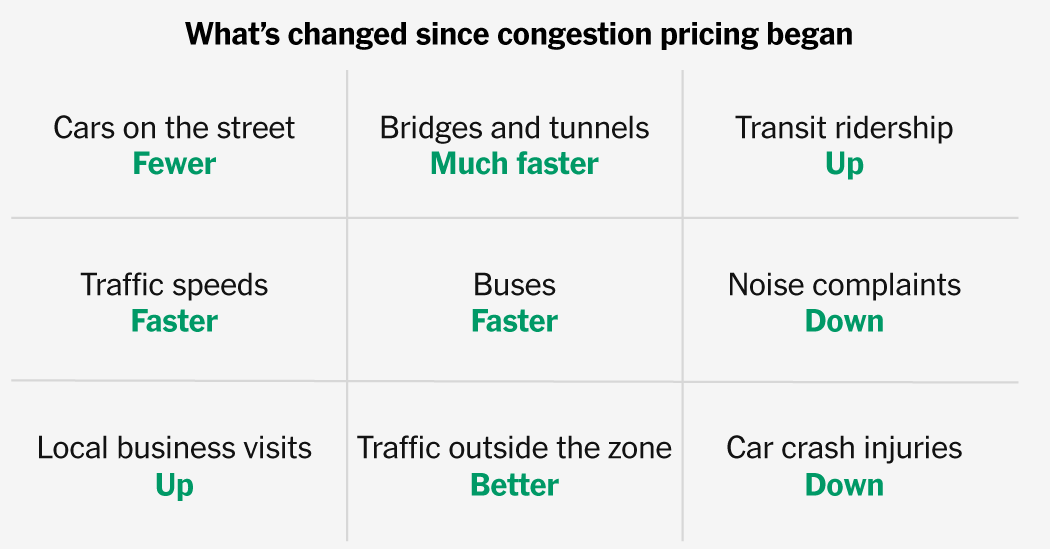

One year after New York City began charging most drivers to enter Manhattan below 60th Street, roughly 73,000 fewer vehicles enter the central business district each weekday — about 27 million fewer entries in the program's first year. Traffic speeds, bus performance and subway ridership have improved, while the toll has generated several hundred million dollars for transit projects and faces ongoing legal uncertainty.

What happened

On Jan. 5, 2025 the city began charging most drivers who enter Manhattan below 60th Street; peak tolls rise to $9 during busy hours. Compared with pre-toll trends, daily personal vehicle entries to the central business district are down by about 73,000, a roughly 11 percent decline that amounts to about 27 million fewer entries in the first year. Vehicle speeds rose across the region, with the largest gains concentrated on key bridges and tunnels into Manhattan; some chokepoints saw increases measured in the tens of percent. Bus routes that cross the zone show modest speed improvements, and paid transit ridership — especially on the subway — has continued to climb. The program is projected to net roughly $550 million after expenses in its first year, funds allocated for public-transportation upgrades. At the same time, individuals report changed travel patterns and some say the fees create a financial strain. A federal legal challenge to the program remains unresolved.

Why it matters

- Fewer private vehicles entering central Manhattan directly reduces congestion on streets and approaches, affecting travel times across the region.

- Faster traffic and improved bus speeds can increase reliability for transit-dependent commuters and longer-distance travelers.

- Revenue from the tolls provides a dedicated funding source for M.T.A. projects, supporting maintenance and upgrades.

- Behavioral changes — from altered departure times to fewer trips — show how pricing can shift travel choices, with distributional effects for households.

Key facts

- Program start date: Jan. 5, 2025.

- Peak toll for most drivers entering below 60th Street: $9; tolls drop after peak periods (example drop to $2.25 after 9 p.m.).

- Average reduction: about 73,000 fewer personal-vehicle entries per weekday — roughly an 11% decline and ~27 million fewer entries in the first year.

- Vehicle speeds during peak toll hours rose by roughly 4.5% inside the congestion zone, 2.2% near the zone and 1.4% elsewhere in New York City (Jan–Nov comparison, 2024–25).

- Some bridge and tunnel approaches saw much larger gains; for example, the Lincoln Tunnel inbound speeds increased by about 51% during weekday morning commutes.

- Bus speeds on local routes in the zone improved (~+2.4%), while express routes in the zone rose ~2.0%; elsewhere gains were smaller or negative for express routes.

- Paid transit ridership increased across modes; subway ridership is about 300,000 riders higher per day compared with 2024.

- Projected net revenue in the first year is roughly $550 million after expenses, about $50 million more than initially forecast.

- The M.T.A. has met most of its stated goals so far, according to available data and outside analyses.

- A federal legal challenge seeking to halt the program had not been resolved as of the reporting date.

What to watch next

- Outcome of the pending federal legal challenge that could affect the program's future.

- How the M.T.A. allocates and deploys the projected toll revenues for transit projects and whether delivery meets timelines.

- Whether observed increases in transit ridership and speed gains are sustained over multiple years as travel patterns stabilize.

Quick glossary

- Congestion pricing: A policy that charges drivers a fee to enter a defined area or roadway during certain times to reduce traffic and raise revenue.

- Central business district: The core commercial area of a city; in this report it refers to parts of Manhattan below 60th Street and adjacent roadways.

- M.T.A.: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the regional agency responsible for public transit in New York City and surrounding areas.

- Paid transit ridership: The number of trips taken on public transit for which riders paid fares, including subways, buses and commuter rail.

- Bridge/tunnel chokepoints: Major crossings that concentrate traffic into and out of Manhattan and can create significant delays when congested.

Reader FAQ

How much is the congestion fee?

Peak charges for most drivers are $9 to enter Manhattan below 60th Street, with lower rates outside peak hours (examples in the source include a drop to $2.25 after 9 p.m.).

How many fewer cars are entering Manhattan?

Daily personal-vehicle entries to the central business district are down by about 73,000 on average, roughly an 11% decline and about 27 million fewer entries in the first year.

Has traffic gotten better?

Available data show higher average vehicle speeds during peak toll hours across the zone and surrounding areas, with especially large gains at some bridges and tunnels.

Is the program secure from legal or political challenge?

not confirmed in the source.

Since congestion pricing began one year ago, about 11 percent of the vehicles that once entered Manhattan’s central business district daily have disappeared. This may not seem like a lot….

Sources

- 27M Fewer Car Trips: Life After a Year of Congestion Pricing

- Less Traffic, Better Transit: On Its First Anniversary, Governor …

- One Year In, Congestion Toll Yields Gains for Manhattan …

- Congestion pricing: 27 million fewer vehicles entered …

Related posts

- Vietnam to Ban Unskippable Ads; Skip Button Must Appear Within 5 Seconds

- Mamdani Signs Two Executive Orders Targeting Junk Fees and Hidden Charges

- Gemini protocol deployment statistics: snapshot of the geminispace, Jan 6 2026