TL;DR

An essay argues that cosmology may be in the early stages of a scientific revolution driven by persistent tensions between observations and our theories of gravity. Historical successes—like Neptune’s prediction and Einstein’s general relativity—contrast with persistent anomalies such as galaxy rotation curves that have led to the dark matter hypothesis but no direct detections.

What happened

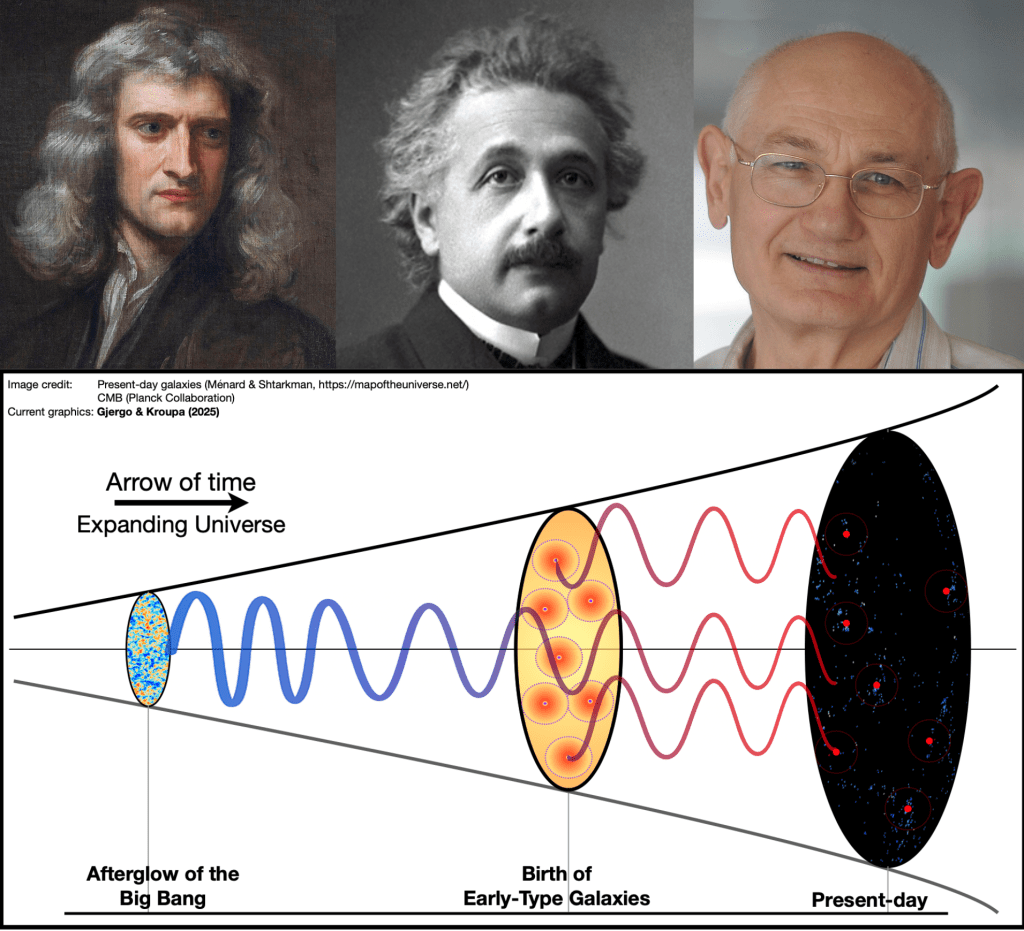

The author traces a long history in which astronomical anomalies have forced shifts in scientific thinking. Early advances—Copernicus, Kepler and Newton—unified planetary motion, and Newton’s inverse-square law proved predictive across the solar system. In the 19th century, deviations in Uranus’s orbit were explained by predicting a new planet (Neptune), a triumph for Newtonian theory. Later, unexplained aspects of Mercury’s motion resisted a similar ‘‘missing mass’’ fix and were resolved only when Einstein introduced general relativity in 1915. Einstein’s framework later produced successful, novel predictions: black holes (imaged by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019) and gravitational waves (first detected in 2015). The essay argues, however, that in the weak-gravity regime conventional assumptions may fail: observations since the 1930s (Zwicky’s cluster work) and especially galaxy rotation curves studied by Vera Rubin in the 1970s show velocities inconsistent with predictions from visible mass, prompting the dark matter paradigm. Despite its dominance, dark matter has not been found in laboratory experiments, leaving open the possibility that modifications to gravity — not unseen mass — could be required.

Why it matters

- If current gravitational theory fails in some regimes, fundamental physics and cosmological models may need revision.

- The unresolved discrepancy between astronomical dynamics and visible mass challenges whether unseen matter or new gravitational laws best explain observations.

- How scientists respond to anomalous data—by seeking missing components versus revising theories—shapes research priorities and funding.

- Decisions about theory versus data affect interpretation of cosmological history, structure formation, and the inferred composition of the universe.

Key facts

- Kepler derived empirical laws of planetary motion in the early 17th century; Newton later showed they follow from an inverse-square law of gravitation.

- Urbain Le Verrier and John Couch Adams independently predicted Neptune’s position in 1845 to resolve Uranus’s orbital deviations.

- Mercury’s anomalous perihelion precession could not be explained by Newtonian corrections or a hypothesized planet Vulcan; Einstein’s 1915 general relativity accounted for it.

- General relativity produced later novel confirmations: the first image of a supermassive black hole’s accretion structure (M87) in 2019 and initial detection of gravitational waves in 2015.

- Edwin Hubble used redshift measurements in 1929 to show galaxies recede with velocity proportional to distance, indicating cosmic expansion.

- Fritz Zwicky (1933) reported unexpectedly high galaxy speeds in clusters; Vera Rubin’s work in the 1970s found flat galactic rotation curves inconsistent with visible mass distributions.

- The dominant response to these discrepancies has been the dark matter hypothesis: an unseen form of mass inferred solely from gravitational effects.

- Direct-detection experiments on Earth have so far reported no confirmed identification of dark matter particles.

- The author frames current cosmology as possibly undergoing a slow, ongoing scientific revolution driven by these long-standing tensions.

What to watch next

- Results from ongoing and future direct-detection dark matter experiments and their implications for the dark matter hypothesis.

- New and higher-precision astronomical measurements of galaxy rotation, cluster dynamics and large-scale structure that test gravity at low accelerations.

- Theoretical developments proposing and testing modified-gravity frameworks as alternatives to dark matter.

Quick glossary

- General relativity: Einstein’s theory describing gravity as curvature of spacetime produced by mass and energy; it replaces Newtonian gravity in strong-field or relativistic regimes.

- Dark matter: A hypothesized form of matter inferred from gravitational effects on visible matter, radiation and large-scale structure, but not directly observed electromagnetically.

- Redshift: The increase in wavelength (shift toward the red) of light from objects moving away from the observer, used to infer cosmic velocities and distances.

- Gravitational waves: Ripples in spacetime produced by accelerating masses, detectable as tiny changes in distance between objects; first directly detected in 2015.

Reader FAQ

Does the author claim general relativity is wrong?

The source argues that while general relativity has passed many tests, there are persistent anomalies in weak-gravity regimes that raise questions; it does not assert a definitive refutation.

Has dark matter been directly detected?

No confirmed direct detection of dark matter particles on Earth is reported in the source.

What was Vulcan?

Vulcan was a hypothesized planet proposed to explain Mercury’s orbital anomaly; searches did not find it and the anomaly was later explained by general relativity.

Are galaxy rotation curve discrepancies a new observation?

No. The mismatch between observed galactic rotation speeds and those predicted from visible mass has been documented since at least the 1970s and earlier cluster work in the 1930s.

JANUARY 15, 2026BLAIR FIX An Unfolding Scientific Revolution in Cosmology Download: PDF | EPUB | MP3 | WATCH VIDEO There is a tendency, among both scientists and non-scientists, to assume…

Sources

Related posts

- Why one developer still has major gripes with Prolog’s language design

- Why Senior Engineers Let Bad Projects Fail: Managing Influence Wisely

- How I Learned Programming: Hands-On Practice, Community, and Curiosity