TL;DR

UC Berkeley’s SETI@home project analyzed 21 years of Arecibo radio data processed by millions of volunteer home computers and initially identified about 12 billion interesting events. After a decade-long vetting effort the team reduced those to roughly a million candidates and then 100 targets now being followed up with China’s FAST telescope; FAST observations have not yet been analyzed.

What happened

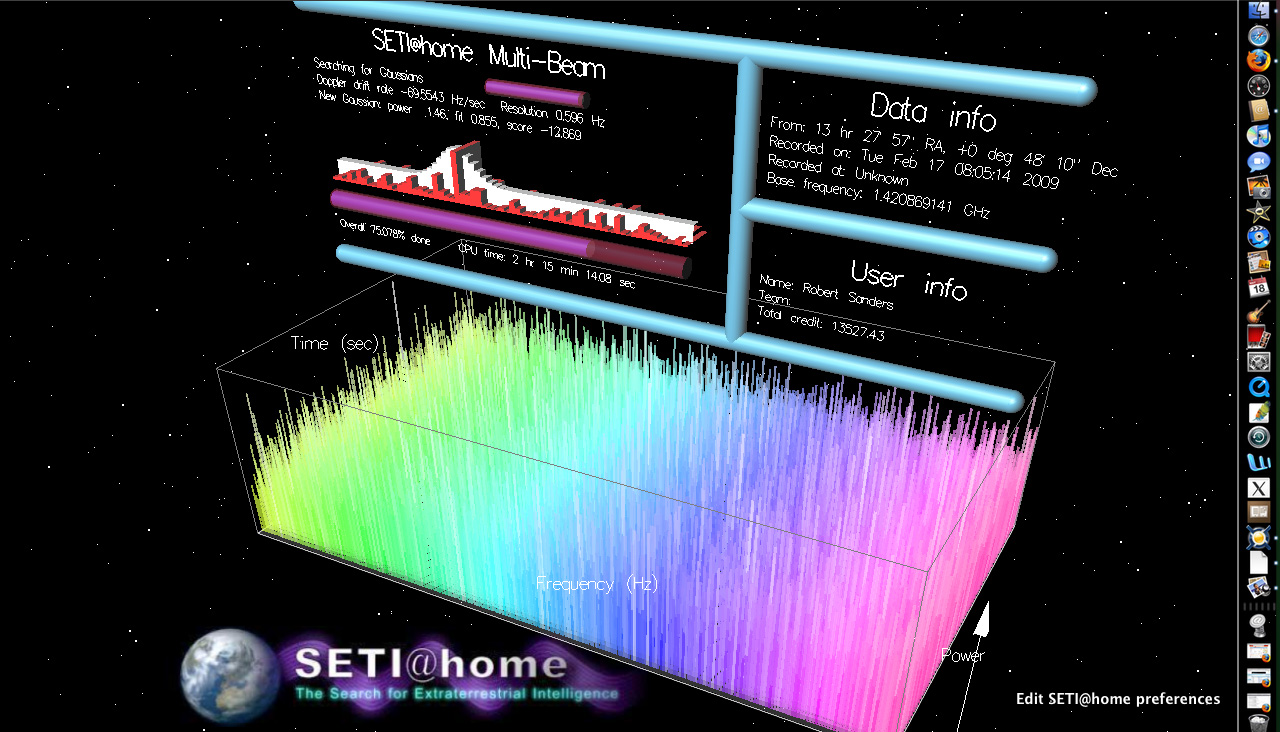

Launched in 1999, SETI@home used distributed computing on volunteers’ desktops to search Arecibo Observatory recordings for narrowband technosignatures. Between 1999 and 2020 the project’s software flagged about 12 billion brief energy spikes in frequency and sky position. Over roughly ten years the team developed methods to triage that volume, winnowing the detections to about a million candidate signals and then isolating roughly 100 that merit renewed observation. To validate their pipeline, researchers injected around 3,000 artificial “birdie” signals into the data stream and used those to estimate sensitivity. Since July the group has been pointing the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) at those 100 targets, though the FAST data have not yet been analyzed. Team leads say they do not expect an extraterrestrial discovery but emphasize the project’s methodological lessons for future searches, especially around radio interference and search sensitivity.

Why it matters

- Demonstrates the scale of data and false positives modern radio SETI must handle — billions of candidate events.

- Highlights the importance of robust RFI (radio frequency interference) filtering and knowing what is excluded when culling candidates.

- Validates distributed computing as a way to explore wide parameter spaces (e.g., many Doppler drift rates) that are costly for single facilities.

- Establishes a quantified sensitivity baseline and procedural lessons that can inform future sky surveys and targeted searches.

Key facts

- SETI@home ran from 1999 to 2020, using data recorded at the Arecibo radio telescope.

- Volunteer computers initially flagged about 12 billion brief signal detections.

- A multi-year analysis reduced those detections to about one million candidates and then to roughly 100 signals chosen for follow-up.

- Researchers injected roughly 3,000 synthetic signals into the pipeline to test detection performance and sensitivity.

- China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) has been pointed at the 100 targets since July; those FAST observations are not yet analyzed.

- Two papers describing the SETI@home results were published last year in The Astronomical Journal.

- The project scanned tens of thousands of possible Doppler drift rates to account for relative motion between Earth and potential signal sources.

- SETI@home relied on commensal observing at Arecibo, which covered about a third of the sky and observed many regions 12 or more times.

- At its peak the project drew participation from millions of volunteers; early projections expected 50,000 but it reached about a million users within a year.

What to watch next

- Analysis results from the FAST observations of the 100 targets — not confirmed in the source.

- Whether any of the 100 candidates are observed to repeat or persist in independent follow-up — not confirmed in the source.

- Subsequent publications or data releases detailing the FAST follow-up and any refinements to SETI search methods — not confirmed in the source.

Quick glossary

- Distributed computing: A method of breaking a large computation into smaller tasks and running them on many separate computers, often volunteered by individuals.

- Radio frequency interference (RFI): Unwanted radio signals from human-made sources (satellites, broadcast transmitters, microwave ovens, etc.) that can mimic or obscure astronomical signals.

- Narrowband beacon: A signal concentrated in a very small range of frequencies, often considered easier to detect against background noise and a plausible design for an intentional transmitter.

- Doppler drift: A change in observed frequency over time caused by relative motion between a signal source and the observer; searches must account for many possible drift rates.

- Technosignature: A measurable sign of technology or engineered activity from an extraterrestrial source, such as an engineered radio transmission.

Reader FAQ

Did SETI@home find definitive evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence?

No. The project identified 100 targets for follow-up but has not produced a confirmed extraterrestrial detection.

Where did the data analyzed by SETI@home come from?

The project analyzed radio observations recorded at the Arecibo Observatory between 1999 and 2020.

Are the 100 signals confirmed?

They are flagged for follow-up; FAST observations have been collected but their analysis is not yet complete.

How did researchers test their detection process?

They inserted about 3,000 synthetic signals into the data pipeline to blind-test the system and estimate sensitivity.

Research, Science & environment, Technology & engineering For 21 years, enthusiasts used their home computers to search for ET. UC Berkeley scientists are homing in on 100 signals they found….

Sources

Related posts

- A Slow-Burning Scientific Revolution in Modern Cosmology: Reassessing Gravity

- Why one developer still has major gripes with Prolog’s language design

- Why Senior Engineers Let Bad Projects Fail: Managing Influence Wisely